If you grew up as a gay man in the UK during the 1980s or 90s, you might feel as though you’re carrying something that your peers are not. It isn't always a loud or obvious burden. Often, it's a quiet hum of anxiety in relationships, a lingering sense of being an imposter, or a persistent, low-level shame you can’t quite name.

The purpose of this article is to explore the specific, long-lasting effects of Section 28.

We will connect a piece of political history to the very personal, developmental consequences it had on a generation. My aim, as a therapist who works extensively with gay men and queer people, is to offer a framework for understanding these feelings and to validate that your experience is a perfectly logical response to an illogical time.

What Was Section 28? A Clause of Invisibility

For those who didn't live through it, or for whom the memory is hazy, it’s worth being clear.

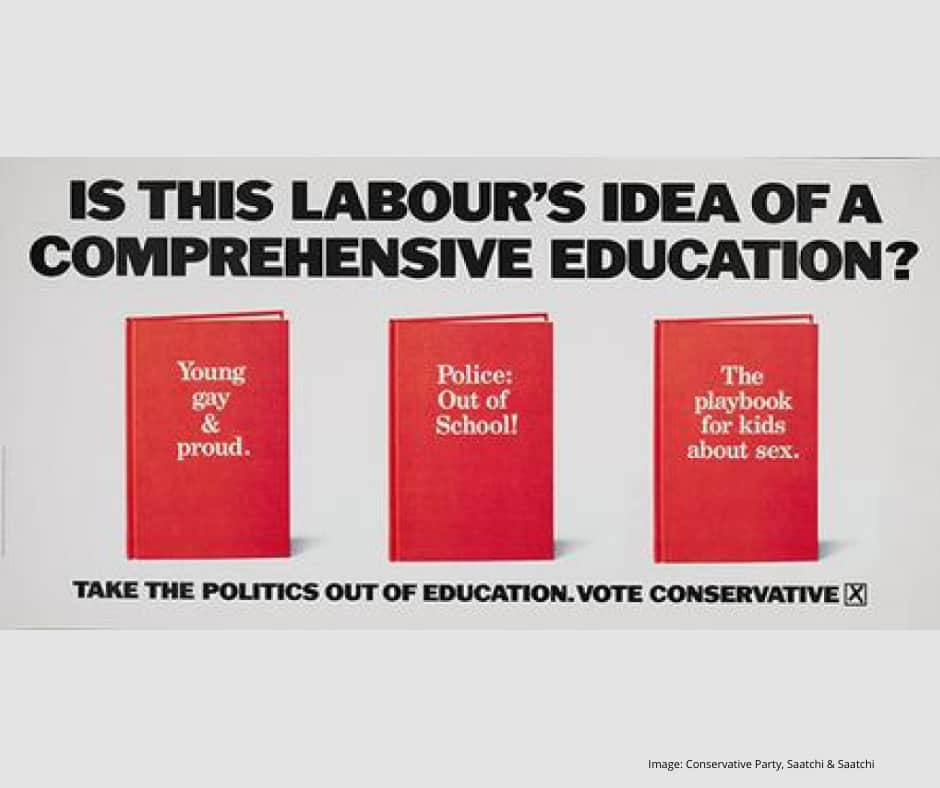

The moral panic we see today surrounding trans people and other queer identities isn't new. Back in 1987 the Conservative Party publicised general election campaign poster accusing the Labour Party of politicising education.

Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 was a piece of legislation that banned local authorities - and therefore, most schools - from "promoting homosexuality" or publishing material with the intention of promoting it. It also prohibited teaching "the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship."

It was enacted in a climate of moral panic, fuelled by the AIDS crisis and years of hostile media coverage. The law’s real power wasn't just in what it banned, but in the silence it created.

It was a clear, institutional message delivered to you during your most formative years: who you are is unmentionable. It is shameful, controversial, and must not be spoken of. This enforced silence became the soil in which deep-seated psychological challenges could grow.

The Psychological Echo: Growing Up in the Shadow of the Law

A political act has personal consequences. The silence of Section 28 didn’t stay in the corridors of Westminster; it entered the school corridors, the playgrounds, and eventually, our own heads. Here are some of the ways the developmental impact of shame and invisibility can manifest in adulthood.

The Ghost of Prejudice: Internalised Homophobia

When the world around you treats an intrinsic part of your being as something too dangerous or shameful to even name, you learn to treat it that way yourself. This is the root of internalised homophobia.

It’s not necessarily a conscious self-hatred. It’s far more subtle.

-

It can be the flash of discomfort you feel when you and your partner hold hands in a new place.

-

It might be the automatic self-censoring you do in a new workplace, calculating whether it’s ‘safe’ to mention your weekend.

-

It’s the nagging voice that questions your validity, suggesting you’re ‘making a fuss’ or that your relationship isn’t as real as a straight one.

This is the ghost of Section 28. It's a teacher’s silence, the memory of erasing a drawing, the fear of a punchline in the schoolyard. It’s an understandable response to being told, implicitly and explicitly, that a core part of you was a ‘problem’.

Growing Up Without Mirrors: The Lack of Gay Role Models

Healthy identity development relies on seeing yourself reflected in the world. You need ‘mirrors’ to confirm that your way of being is possible, valid, and can lead to a good life. For those growing up gay in the 80s UK, those mirrors were systematically smashed.

There were no positive gay characters in school library books. There were no discussions of historical figures who were gay. There were no teachers who could be safely out. This meant you were building a sense of self from scratch, often using scraps of information gleaned from stereotypes, sensationalised news reports, or coded references.

The long-term result can be a feeling of fundamental instability. You may feel like you’re winging it in life, especially when it comes to relationships and building a future. You didn’t have the same roadmaps for adulthood that your heterosexual peers took for granted.

Intimacy and the Expectation of Rejection

When your formative years are spent trying not to be ‘found out’, you become an expert in threat detection. You learn to read rooms, scan for danger, and anticipate rejection. While this is an incredibly effective survival skill for a teenager in a hostile environment, it can be detrimental to forming secure, intimate bonds as an adult.

This can manifest as:

-

Difficulty with trust: A deep-seated belief that if someone truly knew you, they would leave.

-

Relationship anxiety: Constantly looking for signs that things are about to go wrong, even when they’re going well.

-

Avoidance of vulnerability: Keeping partners at an emotional distance to pre-empt the pain of potential abandonment.

-

Push-pull dynamics: A cycle of craving closeness and then pushing it away when it becomes too real or intense.

It makes perfect sense that if you were taught that your authentic self was unacceptable, you would struggle to believe it could be accepted, let alone cherished, by another person.

Moving Through: Ways to Build a More Integrated Self

Acknowledging the impact of the past is the first step.

The next is finding ways to live more freely in the present. Here are some observations from my practice on how men have found their own paths forward.

1. Name the Source

The first, and perhaps most powerful, step is to correctly label the feeling. That vague sense of shame or 'wrongness' is not a character flaw. It is a political and cultural artefact you were forced to carry.

When that critical inner voice pipes up, practise observing it and saying to yourself, “That is not me. That is the echo of Section 28. That is the sound of a 1980s tabloid headline.” By externalising it, you strip it of its power and see it for what it is: an old, outdated message, not a present-day truth.

2. Actively Seek Out Your History

You were denied mirrors then, but you can build a hall of mirrors for yourself now. This means actively seeking out the stories, art, and histories that were hidden from you.

Look beyond the trauma narratives

Read about the vibrant queer communities that existed before the AIDS crisis. Explore the history of the Gay Liberation Front, the defiant joy of early Pride marches, or the lives of artists and thinkers who lived full, complex queer lives a century ago.

Find stories from men of the generation before you

There are countless documentaries, oral history projects, and podcasts where older gay men talk about their lives. Hearing them speak about navigating love, work, and friendship provides the kind of roadmap you were never given. This isn’t about finding a single ‘role model’, but about populating your mind with a rich diversity of possible lives.

3. Redefine Connection on Your Own Terms

A huge part of heteronormativity is the assumption that the ultimate goal is a monogamous, romantic partnership that sits at the top of a hierarchy of relationships.

Section 28 reinforced this by labelling everything else a pretended family relationship. You have the opportunity to reject that hierarchy entirely.

Connection can be found in the deep, sustaining power of platonic friendships. These are not a consolation prize; for many, they are the central, life-affirming bonds.

Practise Small Acts of Self-Trust

After years of self-censoring, trusting your own instincts can feel foreign. The work here is to start small. It’s about making a tiny choice that honours your authentic self, and then sitting with the fact that the sky did not fall in.

-

It could be as simple as making a comment at work that references your partner, without apology or explanation.

-

It might be choosing to spend a weekend pursuing a solitary hobby you love, rather than doing what you feel you ‘should’ be doing to find a partner.

-

It could be speaking up when someone makes a lazy, heteronormative assumption in conversation.

Each small act is a way of telling your nervous system, which was trained for danger, that the environment has changed. You are the adult in the room now, and you get to decide what is and isn't safe.

A Grounded Hope

The legacy of Section 28 is real. The effects of section 28 are woven into the fabric of many gay men's lives in the UK. Acknowledging the anger, grief, and frustration over what was taken from you - a peaceful, accepting adolescence - is a crucial part of the process.

You are not broken, and you are not alone in this feeling.

But the story does not end there. While the echoes of that silence may never disappear completely, their volume can be turned down. By understanding their source, by consciously building a world rich with connection and history, and by practising trust in yourself, you can build a life of profound integrity, intimacy, and joy. It is a life you have always deserved.

A Note from My Practice

If this article has resonated with you, simply sitting with that recognition is a significant step. Exploring these feelings, whether on your own or with others, is a valid and worthwhile process.

I am a BACP accredited therapist with a practice dedicated to providing GSRD (Gender, Sex, and Relationship Diversity) and trauma-informed therapy for gay, bi, trans, non-binary, questioning, queer - and straight - individuals.

If you feel that speaking with a professional who understands this specific context could be helpful, I invite you to learn more about me. You can find details and book an initial, no-obligation consultation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What exactly did Section 28 ban?

Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 prohibited local authorities in the UK from "intentionally promoting homosexuality" or teaching "the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship." This effectively silenced any positive or neutral discussion of being gay in most schools.

How does internalised homophobia actually show up in daily life?

It often appears as chronic self-doubt, a heightened sense of anxiety in social situations, difficulty accepting compliments, or a persistent feeling of being ‘less than’ your heterosexual peers. It can also manifest as being overly critical of other openly queer people.

I don't feel 'traumatised', just a bit off or anxious in relationships. Is this still related to Section 28?

Trauma isn't always about a single, major event. The developmental impact of growing up under the constant, low-level stress and shame of Section 28 has the potential to wire someone's nervous system to expect rejection, which can absolutely manifest as feeling 'off' or anxious in adult relationships.

Is it too late to deal with the effects of growing up in the 80s and 90s?

Absolutely not. In fact, many men only begin to connect the dots and understand the impact of this history in their 40s and 50s. Adulthood provides the safety, perspective, and resources to finally address these foundational experiences. It's never too late to build a more integrated and fulfilling life.

What should I look for in a therapist to discuss this?

Look for a therapist who is, at a minimum, ‘GSRD-aware’, LGBTQ+ affirmative or, ideally, an affirmative therapist who specialises in this area. This means they won't just tolerate your identity but will understand the specific historical and cultural context - like the effects of section 28 - that has shaped your experience. Checking if they are a member of a professional body like the BACP is also important.